We Turned Down A "Once In the Lifetime Opportunity" to Build the Company of a Lifetime

Josie SivignyWhen we first decided to build our company, it was in the beating heart of Silicon Valley. At the time, we were both working at an early-stage software company, flush with funding and fantasizing about making millionaires out of all of its employees. Only now, with the benefit of hindsight, can we fully understand that this was a kind of mass delusion.

There’s a looming consensus on so-called business truths that infects new ventures. Take, for instance, the deep push to raise VC money. When we, somewhat innocently, asked if we absolutely had to go that route, we had some VCs laugh in our face and derogatorily refer to us as a “lifestyle business” if we refused their massive checks.

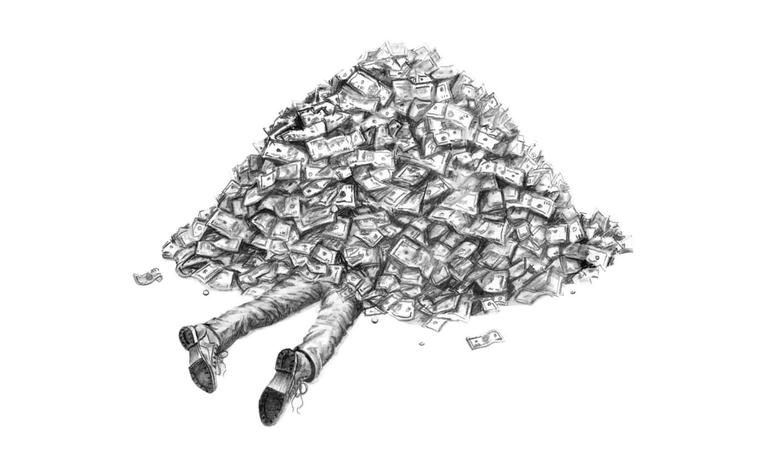

Many founders of companies genuinely believe all they need to do is hack together a monstrous hype machine as quickly as they can, build the perception of consumer buzz for the sake of investors, allow their equity to vest, and then finally get acquired for their golden payday.

We ended up proving that whole thesis wrong. Since our original $6,000 investment from our own savings, we’ve grown Tuft & Needle to $100 million in revenue and 100 employees, with only our month-to-month profits and no outside investors.

This stands in contrast to an era in which founders are given phantom money for faux products — a distorted reality in which there’s technically a business, but little to show for it. A faux business of this kind might have millions in funding, but no one to buy the dog food. They may have a sky-high valuation, but no revenue.

Some basic myths form the core of these phantom businesses. Take, for instance, the idea that “the stock is the product.” Although this phrase was used satirically in the show “Silicon Valley,” it would surprise most people to learn that many founders of companies genuinely believe all they need to do is hack together a monstrous hype machine as quickly as they can, build the perception of consumer buzz for the sake of investors, allow their equity to vest, and then finally get acquired for their golden payday. You’ll listen to them wax on about valuations, funding rounds, and other financial machinations — but you’ll hear not one word about the business or what it does.

We can’t take all the credit and say that we had the wisdom and the willpower to say “no” to investors from the very beginning. Funding is alluring — who could immediately say no to the prospect of a full bank account, the ability to hire everyone you need, promote your brand to the world, and grow like crazy? Or at least that’s how we imagined it.

Our business started simply as a problem we wanted to fix for ourselves, so we had little idea what to expect once the investors came knocking on our door. Toward the end of our first full year, closing out with a million dollars in sales, we received our first investor inquiry. Here we caught wind that a “yet-to-be-announced” competitor was in the process of raising a substantial round of funding. “You guys should take money, too, or else you’ll be squashed. Look at Uber versus Lyft and see what happened there. There’s still time to catch up and get ahead of it.” After this competitor’s public launch, we received a flood of inquiries from dozens and dozens of blue chip VC firms, A-list celebrities, and billionaire family offices looking to get in on the action. Our phone was ringing off the hook.

####“Why don’t you each take a few million ‘off the table’ to offset risk from the chance that things don’t work out?”

Investors waved their bags of money in front of our eyes. As soon as we got caught up in the lofty-sounding language of venture capital — valuations, multiples, liquidation preferences, vesting, and so on — we felt important and validated. Investors shot their term sheets our way, but the numbers seemed random and all over the place — one would say $80 million while another $150 million. All the numbers began blurring together, and our sense of reality became centered around a financial spreadsheet. These people wanted to give us money, and lots of it, too — figures that we had only previously read about in the newspapers. With a sly wink, they suggested to us — scrappy co-founders who had been reinvesting everything back into our business — “Why don’t you each take a few million ‘off the table’ to offset risk from the chance that things don’t work out?”

The business community seems to agree: “Always take the money when you don’t need it.” With the benefit of hindsight, we realized that all our motivations for raising investor capital were either fear-based or greed-based: from being overlooked as a non-player in the press, to getting shut out of the market by competition, to the economy tanking due to a recession. When the seed of temptation was planted, it began sprouting and took us in a direction that had never crossed our minds before: driving the hockey stick of perceived company valuation, planning an exit with an IPO or acquisition, outsourcing our customer service, and so on.

We had our backs against the wall, facing the biggest opportunity of our lifetime, sweating bullets because we were questioning our moral compass and all the things we had once stood for. How much did we care about our product? Did we actually think we were going to change our industry? Why were we doing this? Outside funding can be a different kind of “golden handcuffs”: you forget how business should be done, and you ignore a more objective, incorruptible exploration of what is good for the customers and what is good for the employees.

All around us, we see corporate greed running rampant. Startups peacock to hypnotize investors with the highest perceived valuations. Marketers pull out all the manipulative gimmicks in a salesman’s bag of tricks. And manufacturers outsource to the lowest-bidding factories, using cheap labor to serve customers, and automating in an effort to completely eliminate the human side of business.

What drives all these decisions? Investor-backed companies answer to their shareholders first and foremost. Outside funding brings expectations, since investors need to get paid. Where does that money come from? The company’s pocket, which they need to make back in some way: the companies’ prices have to be higher, they need to run continuous waves of “discounts” to drive revenue, and set up press gimmicks to please existing investors and woo new ones. All of this costs the customer in the end. Not only does this mean you’re sacrificing money from your own wallet, but the level of service the company can provide you is also sacrificed. The true cost of higher prices and perceived discounts is subsidized by customers, who are ultimately paying to be marketed to, and who are padding investors’ pockets, along the way.

Having been on the other side, as consumers and as employees, we knew there had to be a better way. But that kind of change has to happen from within. “If you see that some aspect of your society is bad, and you want to improve it, there is only one way to do so,” Leo Tolstoy said. “You have to improve people. And in order to improve people, you begin with only one thing: you can become better yourself.”

When we quit our jobs to start our own business, we left behind the sheltered comforts of Silicon Valley, the quintessential startup playground. Everyone said we were crazy for starting a mattress company. But even more baffling to them was our trying to make a go at it with our own personal savings — and in Phoenix, Arizona at that.

But these decisions were fundamental and transformative for us. They allowed us not only to escape the homogenous mindset of how things “need to be done,” but also to find and build an environment where we could set off for a journey of self-inquiry about the truth: the truth about how business should be done and the truth about how you can live a meaningful life. We stepped down into the abyss and we’ve never looked back.

We believe that there can be a better world, so we feel a moral obligation to do what we can for change, even if this leads our path to a dead end.

Tuft & Needle has been somewhat of a sandbox for us to experiment with solutions to these problems in the corporate world, along the way building the sort of honest company we’ve always wanted to be a part of ourselves. As we hacked our way through the brush into the unknown, other passive bystanders chuckled and pointed a patronizing finger calling us “cute” and “millennial” in the way we were trying to change an industry. We believe that there can be a better world, so we feel a moral obligation to do what we can for change, even if this leads us to a dead end. Better that, we thought, than becoming another soulless corporation displayed in an investor’s trophy case.

“Free money” is never free. The artist Hugh MacLeod said that what you make …

“suffers the moment other people start paying for it. The more you need the money, the more people will tell you what to do. The less control you will have. The more bullshit you will have to swallow. The less joy it will bring.”

We wholeheartedly agree with this sentiment as it applies to building a business. Saying no to investors was a risk to our livelihood, but also liberated us for the future. Rather than gambling on mergers, acquisitions and IPO’s, we took a risk in the opposite direction. We burned the boats behind us and re-affirmed our commitment to the original path.

We didn’t start with a “business plan” that was pitched at a startup competition, and we don’t have investors pressuring us to flip the company for an exit. We pioneered this wave of a single model, “universally comfortable” mattress — and there is now a gold rush of over 60 look-a-like brands. Although we’ve grown at a rapid pace, we’ve built and grown our company to prioritize longevity and resilience over speed. Since the beginning, we’ve wanted to build a solid foundation for a good company that will outlast ourselves.

We answer to no one but ourselves and our customers. Ultimately, our company exists to make the best mattress for our customers and to provide the best jobs for our employees.